The Native Roots of American Democracy

Credit for many of our democratic ideals may be due as much to Native American thinkers as to European ones

Where do good ideas come from? American author Steven Johnson argues that they do not spring forth pre-formed from the minds of genius individuals; they emerge through interaction, connection, and play.

This might sound obvious, but the history of democratic ideas is usually about genius individuals: Aristotle, Machiavelli, John Locke, James Madison—take a look, for example, at the table of contents of this popular democratic theory textbook.

Other scholars take the Johnson view. They argue that the emergence of democratic ideas was not the product of brilliant European minds alone, but the result the clash of civilizations—and in particular, the clash of imperial, post-feudal Europe with more egalitarian societies in North America. Some examples:

In The Dawn of Everything (2021), David Graeber and David Wengrow argue that the very concepts of freedom and equality put forward by French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau were likely inspired by the (Native) American, Wendat rhetorician Kandiaronk.

Wengrow and Graeber also raise the possibility that the idea of republicanism, which flowered in Europe in the 1600s, might have been influenced in part by the Tlaxcallan Republic the Spanish encountered in Central America in the early 1500s.

Recent scholarship has taken more seriously the contributions of French feminist writer Françoise de Graffigny, whom Graeber and Wengrow posit might have “formed their first impression of what a welfare state, or even state socialism, might be like by contemplating accounts of the empire in the Andes.”

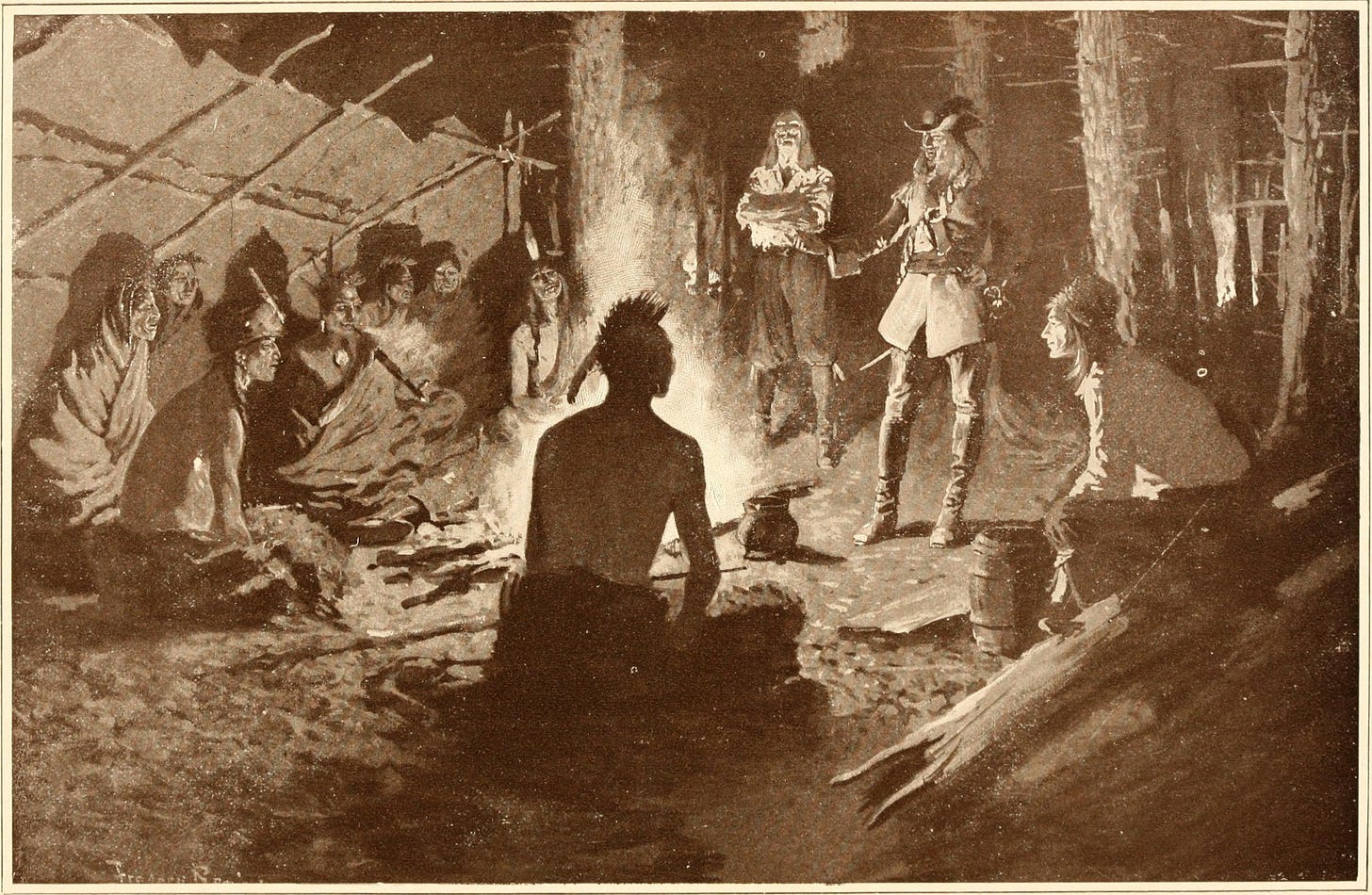

The self-governance of the Haudenosaunee, which according to one author had had been practiced for 15 generations before the arrival of Europeans, “made a lasting impression on the English colonists.” They included one Benjamin Franklin, who would go on to shape the self-governance of the new American colonies. Franklin observed:

“The Indian men, when young, are hunters and warriors; when old, counsellors; for all their government is by the council or advice of the sages. There is no force, there are no prisons, no officers to compel obedience or inflict punishment. Hence they generally study oratory, the best speaker having the most influence.”

The Haudenosaunee peoples and the broader Iroquois Confederacy also inspired the very idea of federalism, that most American of political ideas, as a 1988 Congressional Resolution attests. Their constitution—the Great Law—may date back to the late 12th century, and has some striking overlap with the U.S. Constitution. While not the only inspiration for the Constitution, it seems reasonable to me that the American founders might have snagged more than one good idea from it.

On a personal note, I have been humbled to learn about all of these influences and connections and grateful for scholars’ efforts to lay them out. I am only beginning to consider their implications, including for how we understand and teach American history and democratic theory. And in a particularly fractious time in American history, I’m curious to take another look at those early (Native) American thinkers for clues about how we might recompose a story of America’s future, one that can carry us toward a more perfect union.